Manis javanica Desmarest, 1822

also known as the Malayan PangolinTable of Contents

The Malayan Pangolin is a unique animal that instinctively appears to be a reptile due to its conspicuous scales covering most of the animal's body surface. This mammal lives on a diet of ants and termites, and rolls into a ball of hard scales when provoked. Sadly, this interesting animal is currently endangered, with hunting for its meat, skin and scales as a driver of its massive population decline. While wild populations of Malayan Pangolins still exist in Singapore's forested areas, their numbers continue to decline due to habitat loss and vehicular accidents.

Common Names

- Malayan Pangolin

- Sunda Pangolin

- Scaly Anteater

- Pangolin Javanais (French)

- Pangolin Malais (French)

- Pangolin Malayo (Spanish)

- 穿山甲; Chuān shān jiǎ (Mandarin, Chinese)

Etymology

Manis is based on manes in Latin, meaning ghosts or spirits. It refers to the nocturnal nature of the pangolin as well as its uncommon morphology. The geographical region is referred to in javanica.The English term 'pangolin' is adapted from the Malayan word for a roller, 'peng-goling', alluding to the animals' response to curling into a ball under threat.

Biology of Pangolins

Diet

Pangolins feed on ants and termites (Lekagul & McNeely, 1988) using their unique, long sticky tongue. Their keen sense of smell allows them to find food, and front claws aid in digging up ant nests. Pangolins are known to consume up to 70 million ants a year, and this highly specific diet makes it difficult to keep them in captivity since many fall sick after ingesting foreign food (Save Pangolins, 2012). Watch the video below from 00:48 to observe the Pangolin feeding.

|

| Lioness pawing a curled up pangolin. Photo by David Bygott. |

Behaviour

They are nocturnal creatures that are very solitary in nature and usually stop moving when a human in encountered (Lim & Ng, 2007). Depending on the species, pangolins may only stay on the ground, or only in trees, or a mixture of both, like in the Malayan Pangolin. They are able to climb trees using their prehensile tail. When threatened, they roll themselves up into a ball to protect their soft undersides, as seen above. In some cases they produce a foul smelling chemical in defense as well.

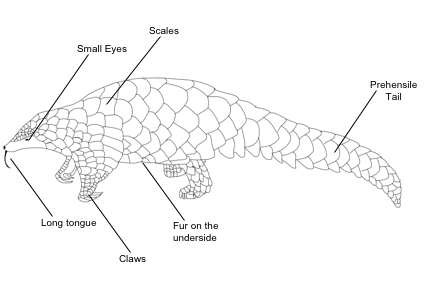

Features of a Pangolin

These creatures do not have teeth but instead have a long tongue adapted to eating ants and termites quickly. This tongue is supported by muscles that start in the animal's pelvis (Wilson, 1994). Individuals have poor eyesight but have a keen sense of smell as well as good hearing, both of which they use to locate their prey.

Continue reading to find out more about their morphology and how to identify the Manis javanica from the other pangolin species.

Reproduction

Offspring are given birth to once each time (Payne & Francis, 1998), yet not many records exist on births per year and other information. Lim & Ng (2007) managed to estimate the gestation time of more than 130 days, and maternal care of about 3 to 4 months, for M. javanica, during which the offspring would often be carried on the tail of its mother (Wilson, 1994).

Not much else is known about the reproduction in pangolins due to their secretive nature and the difficulty in keeping them captive. The Malayan Pangolin has been successfully bred in the Singapore Night Safari before, unfortunately it did not survive very long after birth. The video on the right shows the ultrasound done on Nita the pangolin when she was pregnant.

Ecosystem Roles

Pangolins have been said to control ant and termite populations in habitats that they exist in. Adults may consume about 70 million insects per year (Heath, 1992). The digging action they use during feeding also helps aerate the soil (Heath, 1992).

Distribution

Habitat

Pangolins occur in various habitats including

- grasslands

- tropical rainforests

- hilly areas

- agricultural habitats

Geographical Range of M. javanica (Schlitter, 2005)

|

| Geographical range of the Malayan Pangolin as highlighted by the red oval. Figure by Nicole Lek. |

The Malayan Pangolin occurs naturally throughout Southeast Asia:

- Singapore*

- Peninsula Malaysia*

- Southern Myanmar

- Central and Southern Laos

- Central and Southern Vietnam

- Thailand*

- Cambodia*

- Sumatra*

- Java*

- Borneo*

Pangolins in Singapore

Distribution

View Malayan Pangolin spottings in Singapore in a larger map

Locally, pangolins are mostly restricted to the larger patches of forest like Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve and those in offshore islands of Pulau Tekong and Pulau Ubin. However, pangolins are occasionally chanced upon by members of the public as roadkill. Recently, individuals have also been seen in urban areas like pavements (STOMP, 2012) as well as residential high-rise flats (Teh, 2005). Yet, these areas are always near to patches of forest where they are likely to have wandered off from.

There is a lack of studies on the pangolin populations in Singapore, as well as basic information on the Manis javanica such as its biology and behaviour. Therefore, the number of pangolins here is still unknown, and more research is needed to help inform authorities on effective conservation efforts.

The map above shows some of the previous sightings of the Malayan Pangolin in Singapore, click each location to see the date each was spotted. Many of those reported to be roadkill were collected by representatives of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research as specimens for the museum to study. Several live pangolins have also been spotted walking around in search for food, or simply lying curled up on a pavement. The video below shows a Malayan Pangolin on the move in Labrador Nature Reserve. Have you seen a pangolin in Singapore?

|

| Malayan Pangolin climbing a tree in Bukit TImah Nature Reserve. Photo by Prathini Selveindran. |

Threats to the Malayan Pangolin in Singapore

The population of pangolins in Singapore is decreasing, enough so that it was listed in the Singapore Red Data Book by the NParks. It was labelled critically endangered due to its declining population here. Globally, the species is considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Redlist (2012).

The dropping numbers can be attributed to habitat loss due to deforestation etc, and illegal trade of pangolin meat, scales for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), and more. The former is the primary cause in Singapore, along with roadkill due to the animal's wandering nature. Since most of Singapore's forested areas are surrounded by roads, individuals who stray too far off occasionally meet with an accident while crossing these heavily used roads such as the Bukit Timah expressway. Although the demand for pangolin scales and meat is not high locally, once in a while poachers try to catch them for illegal trade.

In Singapore, it is illegal to remove pangolins from the wild under the Wild Animals and Birds Act. Additionally, those found in nature reserves are protected by the Parks and Trees Act 2005 .If you see a poacher, call NParks at 1800 4717300. To read more about poaching in Singapore, click here.

Have you seen a Pangolin in Singapore?

If you encounter a pangolin in the wild, here are some tips if its alive:

- observe the animal! It isn't everyday you get to see one first hand, so count yourself lucky!

- do not provoke it or touch it.

- report the sighting. The Singapore mammal sightings page gathers information on sightings for education and research.

Threats and Conservation

Threats

The IUCN listed Manis javanica as being endangered (IUCN redlist, 2012), attributing the declining population numbers to high rates of poaching mostly for medicinal purposes. Although the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) listed the Malayan Pangolin in Appendix II and also passed a zero export quota in 2000, individuals are continually illegally hunted in native countries like Vietnam and Thailand, and then shipped mainly to China where there is high demand for the animal's scales and meat for product making, food and for use as medicine. Habitat destruction also contributes to the dwindling numbers.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, pangolin scales, or 穿山甲, are believed to help with deafness, cure malaria, stop excessive crying in children, promote menstruation, and more (Journal of Chinese Medicine, 2012). However, it is known that the scales in question are made up of keratinized cells which originate from the epidermis (Spearman, 1967), thus such medicinal value is unlikely.

|

| Illegally caught pangolins in a market in Myanmar. Photo by Dan Bennett. |

|

| Pangolin soup found in Indonesia. Photo by Wee Lakeo. |

Although pangolin meat is sometimes consumed within the country it is caught in, they are now mostly exported whole because of the high price hunters can fetch for each pangolin, up to US$95/kg in Vietnam (IUCN, 2012). The recent increase in China's affluence have caused demand to rise, with pangolin meat being claimed to cure varying diseases, from skin illnesses to cancer (IUCN redlist, 2012).

The low fecundity rate and dedication of the mother to its young contribute to the inability of pangolin populations to recover over such accelerated rates of hunting. Their defense mechanism of rolling into a ball also makes it easy for poachers to take them away live.

Although much is not known about the illegal trade of pangolins, its large scale is obvious, with about 1200 pangolins being seized in black market raids on several occasions across southeast asia (Abas, 2002). Previously in the 1950s-1960s an estimated 10 000 pangolins were exported from Borneo alone (IUCN, 2012). More recently, raids in Vietnam found a total of 23 tonnes of frozen pangolins uncovered across two occasions in 2008 (Traffic, 2008a). In the same year, police exposed a large scale smuggling exercise in Sabah, Indonesia, and 14 tonnes of frozen pangolins were confiscated. As a result of such massive killings, populations are overall estimated to have dropped 50% over 15 years (IUCN, 2012) with about a 90% drop in numbers in Laos in 10 years (IUCN, 2012).

Among the asiatic pangolins, the Malayan Pangolin is the species most threatened by trade (Brautigam, Howes, Humphreys & Hutton, 1994), with equally high rates of trade seen in M. pentadactyla.

|

| A Pangolin statue used as Donation Collection for Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund. These are found around Singapore. Photo by NIcole Lek. |

National laws have been passed to protect pangolins across countries such as Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia and Philippines. However, stricter enforcement is needed in these areas to ensure illegal hunting and trade do not occur.

Training and increasing the number of rangers and other authorities is one way of increasing enforcement of the laws passed on illegal trade and hunting. Setting up of rescue and rehabilitation centres for pangolins is important in ensuring the survival of pangolins recovered from hunters, etc. Also, increasing the knowledge through scientific research and studies allows for better and more effective conservation methods. These take place throughout the Southeast Asian region although currently not many studies have been done.

Several non-profit groups have also been set up with regards to conserving our Pangolins. Notable ones include the Pangolin Conservation Support Initiative, along with people running the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Programme.

In Singapore, the zoological gardens organized a workshop on conservation and trade of pangolins in the Southeast Asian region in 2008. The convention allowed experts to exchange information on topics like biology and ecology, husbandry and rehabilitation, challenges and threats, and trade and conservation.

What you can do to help

- Do not consume any sort of Pangolin products: meat, medicinal, hide, anything.

- Report wildlife crime. Contact your local authorities if you witness any poaching or illegal activity. For Singapore, call the NParks hotline: 1800 4717300

- Raise awareness. Tell your friends and family the threats to pangolins and what they can do to help.

- Contribute resources and media to various databases to improve educational outreach.

Useful links on Pangolin conservation

- Save Pangolins

- IUCN-SSC Pangolin Specialist Group

- Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Programme in Vietnam

Taxonomy

|

| M. javanica. Photo by Pete Newton. |

Taxonomy ID: 9974

Taxonavigation

Animalia--> Chordata

----> Mammalia

------> Pholidota

--------> Manidae

----------> Manis

------------> Manis javanica

Lineage

Eukaryota; Opisthokonta; Metazoa; Eumetazoa; Bilateria; Coelomata; Deuterostomia; Chordata; Craniata; Vertebrata; Gnathostomata; Teleostomi; Euteleostomi; Sarcopterygii; Tetrapoda; Amniota; Mammalia; Theria; Eutheria; Laurasiatheria; Pholidota; Manidae; Manis

Phylogeny

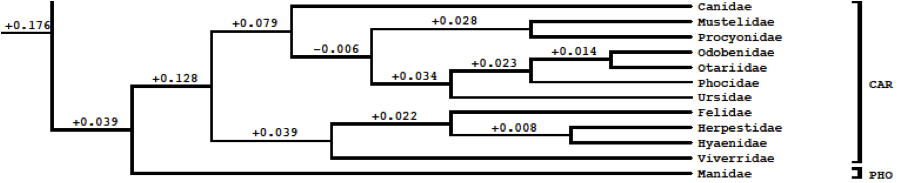

|

| Phylogenetic tree showing Pangolins (Manidae) in relation to other mammal groups. (Beck et al, 2006) |

Pangolins as a taxa (Pholidota: Manidae) was formerly thought to be more related to Xenarthrans, a group made up of armadillos, anteaters, and sloths (Gaudin & Wimble, 1999) than other groups of mammals. However recent studies which included genetic evidences produced a tree with Manidae being more related with Carnivora, forming a monophyletic group with the nested groups, as above (Becks et al, 2006). More studies are yet to be done to confirm the validity of this relationship.

Taxonomic History

The status of the Palawan Pangolin, Manis culionensis (de Elera, 1915) was recognized to be a separate species from M. javanica by Feiler (1998) and then confirmed by Gaubert & Antunes (2005). It was initially listed under Pholidotus culionensis (Elera, 1895) but was much ignored by later literature on the subject. Gaubert & Antunes (2005) have also recently provided discrete morphological characters distinguishing the two species, increasing the total number of pangolin species to 8 globally.

Description (Pocock, 1924)

Head

Small and conical, the Malayan Pangolin's head also bears scales on its dorsal side, continuing from those from its back. These scales extend and almost reaches the rhinarium in the Sunda Pangolin, but stops short before reaching it. Scales nearing the rhinarium are smaller and weaker than the normal ones seen on its back.

Whiskers or vibrissae occur on its face, although they are reduced and short. They are found near the eyes and lips of the pangolin.

Both the eyes and ears of the Manis javanica are relatively small.

Feet

The fore foot comprises of five digits, with the third digit being the largest, followed by the second and forth, and finally the first and fifth digits. The powerful claws protrude out from both the third and the fourth digits. The surface of the foot that faces upwards is coated in scales, while the bottom of the foot is only covered in fur and skin. On the bottom, a single granular pad occurs that covers the whole surface of the foot.

The hind foot also consists of five digits, and are arranged in mostly the same way as the fore foot for Manis javanica. Notably, the claws on the hind foot are almost as long as those in the fore foot, and are probably specialized for climbing trees.

Tail

The Malayan Pangolin's tail is muscular, and it is covered in scales as well. The arrangement of scales allow individuals of Manis javanica to be differentiated from other species. The scales are always symmetrical on the tail, with a line of scales that cut the middle of the tail, extending to its tip.

At the tip of the tail also exists a cutaneous pad that is naked of scales. However, this pad is not smooth but instead have a faint roughness to touch.

Anus and Genitals

The anus occurs in the middle of an eminence, and a pair of anal glands occur to the side of the anus. These glands contain foul smelling chemicals sometimes secreted as part of their defense mechanism. Manis javanica individuals have a very pronounced eminence, while the anus itself sometimes forms a depression on the eminence. Genitalia of both females and males are situated anterior to the anus.

Diagnosis: Manis javanica

There are currently 8 species of Pangolins globally, 4 each in Africa and Asia, including Manis javanica.

African Pangolins:

|

Asiatic Pangolins

|

The species of an Asiatic individual can be narrowed down by its geographical range, since in most areas only one species of pangolin occurs naturally. For example, any pangolin found in the forests of Singapore should be M. javanica since it is the only species there. This cannot be said, however, for parts of Myanmar, Vietnam and Laos, which are shared by both the Malayan Pangolin and the Chinese Pangolin, Manis pentadactyla.

Besides distribution, morphological features can be used to identify the Malayan pangolin. To narrow the species down, it should be noted that the Asiatic pangolins have bristles that protrude in between their scales, unlike the African pangolins (Pocock, 1924).

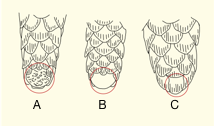

|

| Figure 2: End of tail of 3 Asiatic species. A: M. pentadactyla. B: M. javanica. C: M. crassicaudata. Diagram by Nicole Lek, adapted from Pocock, 1924. |

Of the 4 Asiatic pangolins, M. javanica and M. culionensis are morphologically most similar and are hardest to tell apart. However, examining the end of the tail of the pangolin would differentiate M. javanica and M. culionensis from M. pentadactyla and M. crassicaudata.

As seen in figure 2, the circled area of the end of the tail is indicative of species of the Asiatic pangolins. Tails A and B have a terminal pad whereas tail C only has a terminal scale. However, the terminal pad in A is granular compared to B's which is naked. Tail A belongs to M. pentadactyla, tail B to M. javanica and M. culionensis while C to M. crassicaudata.

Distinguishing M. javanica from M. culionensis is more tricky, with their status as separate species only recently being confirmed. Some diagnostic characters to determine one from the other is seen in the table below (Gaubert & Antunes, 2005).

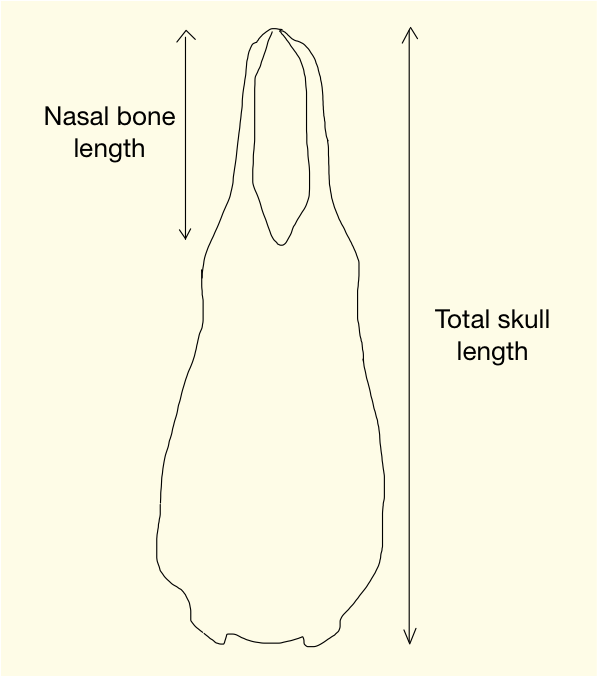

|

| Figure 4: Nasal bone and skull of a pangolin. Figure by Nicole Lek, adapted from Gaubert & Antunes, 2005. |

| Diagnostic characters |

Manis culionensis |

Manis javanica |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Total number of scale rows |

19-21 |

15-18 |

| 2. Size of scales in nuchal, scapular, and postscapular |

Small |

Large |

| 3. Ratio of nasal bone to total skull length |

<1/3 |

>1/3 |

- Scale rows are counted along a virtual line perpendicular to the length of the pangolin, in the centre (Gaubert & Antunes, 2005). M. javanica havefewer scale rows of 15-18.

- Scales in M. javanica are visibly larger.

- The skull is more than 3 times the length of the nasal bone.

Other Useful Links

Literature and References

Brautigam, A., Howes, J., Humphreys, T., & Hutton, J. (1994). Recent information on the status and utilization of African pangolins. TRAFFIC Bull 15:15-22.

Beck, R. M. D., Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P., Cardillo, M., Liu, F. G. R. & Purvis, A. (2006). A higher-level MRP supertree of placental mammals. BioMed Central Evolutionary Biology 6:93.

Chang, A. L. (2006). Tekong's treasures. The Straits Times, 25 April 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

Chou, L. M., Tan, H. T. W & Yeo, D. C. J. (2006) The natural heritage of Singapore. Prentice Hall, Singapore.

Chua, G. (2012). Eye on Singapore; biodiversity in the Singapore story, 8 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

Gaubert, P. & Antunes, A. (2005). Assessing the taxonomic status of the Palawan Pangolin Manis culionensis (Pholidota) using discrete morphological characters. Journal of Mammalogy 86(6):1068-1074.

Gaudin, T. J. & Wible, J. R. (1999). The entotympanic of pangolins and the phylogeny of the Pholidota (Mammalia). Journal of Mammalian Evolution 6(1):39-65.

Gaudin, T. J., Emry, R. J. & Wible J. R. (2009). The phylogeny of living and extint pangolins (Mammalia, pholidota) and associated taxa: a morphology based analysis. Journal of Mammal Evolution 16:235-305.

Heath, M. (1992). Manis pentadactyla. Mammalian Species 414:1-6.

Journal of Chinese Medicine (2012). Use in traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Chinese medicine website, available at http://www.jcm.co.uk/index.php?id=1371. Accessed on 23 November 2012.

Lekagul B. & McNeely J. A. (1988). Mammals of Thailand. Association for the Conservation of Wildlife, Bangkok.

MyPaper (2008). Another Pangolin found dead on road. MyPaper, 8 September 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

Payne J. & Francis, C. M. (1988). A field guide to the mammals of Borneo. The Sabah Society, Kota Kinabalu.

Pocock, R. I. (1924). The external characters of the pangolins (Manidae). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1924:707-723.

Save Pangolins (2012). Found at www.savepangolins.org . Assessed on 14 November 2012.

STOMP (2012). Found at

http://singaporeseen.stomp.com.sg/stomp/sgseen/in_the_heartlands/197714/pangolin_spotted_on_hillcrest_road.html?articlePage=&photosPage=&commentsPage=2 . Assessed on 15 November 2012.

Spearman, R. I. C. (1967). On the nature of the horny scales of the pangolin. Journal of the Linnaean Society (Zoology) 46(310)267-273.

Teh, J. L. (2005). Woman finds this animal in her HDB flat. The New Paper, 23 March 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

The Straits Times (2008). Hanging out in Bukit Panjang. The Straits Times, 30 January 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

The Straits Times (2008). Rare scaly anteater a victim of a road accident. The Straits Times, 11 August 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

The Straits Times (2007). Scaly guest pays a visit. The Straits Times, 26 January 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

TRAFFIC (2008a). 23 tonnes of pangolins seized in a week. TRAFFIC news, 17 March 2008. Accessed 24 November 2012, from

http://www.traffic.org/home/2008/3/17/23-tonnes-of-pangolins-seized-in-a-week.html

TRAFFIC (2008b). Indonesian police smash one of country's largest illegal wildlife smuggling operations. TRAFFIC news, 5 August 2008. Accessed 24 November 2012, from http://www.traffic.org/home/2008/8/5/indonesian-police-smash-one-of-countrys-largest-illegal-wild.html

Wan, C. C. (2004). Wild life at their doorstep. The New Paper, 22 September 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2012, Factiva database.

Wilson, A. E. (1994). Husbandry of pangolins. International Zoo Yb 33:248-251.

Feedback and Comments

Please feel free to leave any comments and experience(s) you have with pangolins! Alternatively, drop me an email at lek_nicole@hotmail.com.